The Climate Impact of a Domain Name

Looking to understand how domain names contribute to climate change? Read on to find out.

A domain name seems like an ethereal thing. It’s hard to imagine that it contributes to global climate change. However, it does. As a foundation of the digital communication infrastructure that sustains the Internet, domain names are part of the carbon footprint of the Information Communication Technology industry that constitutes as much as 4% of global emissions.

To understand how domain names contribute to climate change, it’s worthwhile first to review how the domain name system (DNS) works.

How does DNS work?

When we think of a domain name, we tend to think of it as being a signifier of your brand - it matches your business name or campaign or issue that you’re passionate about. It conveys a message to your customers or audience about who you are and what you value.

In technical terms though, a domain name is the way people find you on the Internet. The servers hosting your website or email address are identified using an IP address. An IP address is a set of digits or letters, such as 99.79.173.28 (IPv4) or f356:763c:3843:b3ef:4dab:abbc:ba4d:66e (IPv6). Neither of these are particularly memorable and you wouldn’t print them on your business card. Using a domain name provides a meaningful address and gives you the flexibility to move your website to different hosts without requiring everyone to update their bookmarks.

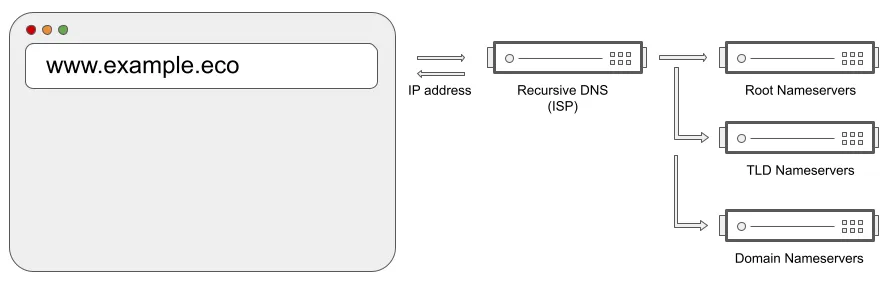

When you enter a URL into your web browser, the first thing that your device does is resolve the domain name into an IP address. Your browser sends a request to a recursive DNS service to perform this lookup. Normally this is the DNS service operated by your Internet service provider (ISP) or mobile telecom.

The reason that it’s called recursive is because a domain name is hierarchical. Each part of a domain name separated with a period (.) is a level in this hierarchy. The DNS lookup traverses this hierarchy going from right to left.

At the top of this hierarchy, you have your top-level domain (TLD), such as .com, .org or .eco. The DNS server first finds out the location of the nameservers that host your domain’s TLD by asking the root nameserver. Next, the TLD nameserver is queried to determine the location of the specific domain. And then finally the domain name’s authoritative DNS service is asked for the IP address of your website. Once this address is returned to your browser from the recursive DNS service, your device knows which IP address to talk to download your website.

This means that every time someone visits your website, there could be up to 3 DNS queries to resolve your domain name.

What is the climate impact of resolving DNS?

As you can see, there are potentially many requests to different servers involved in resolving a domain name into an IP address. Fortunately, DNS requests are tiny (less than 500 bytes) and are resolved quickly. Also there is a lot of caching involved. If you recently looked up a domain name, the odds are it will be cached in your browser, on your device and on your local recursive DNS server.

However, to make all of this work effectively, there is a lot of computer and networking hardware involved. Your Internet Service Provider (ISP) will be running a cluster of recursive DNS servers in a data center close to you. The authoritative DNS service for your domain name (often your domain registrar or web hosting provider) likely runs a global distributed set of DNS servers so that lookups for your domain name will be quick no matter where your website visitors are coming from. Similarly, the TLD nameservers are also running in many data centers around the world. This is to say nothing about all of the telecommunication cables and networking infrastructure that these DNS requests have to pass through.

All of this computer and networking infrastructure requires electricity to run continuously. This electricity is typically supplied by the electricity grid in the region where the data center is located. How cleanly that electricity is generated is a key factor in a domain name’s carbon footprint. While there are many regions where renewable energy is available, having a global presence means unfortunately operating in places where electricity is generated using fossil fuels.

There is also the embedded carbon to account for in the resource extraction, manufacturing, and shipping emissions produced in building and installing all of this communication infrastructure.

How can I calculate the carbon footprint of my domain name?

This is obviously tricky as you won’t have access to all the data you need. However, it is possible to make some rough, high level estimates.

If your DNS provider can tell you how many requests were made for your domain name then this is a decent start - even better if they can tell you which regions or data centers the requests were served from. If this is unavailable, you can use requests to your website as a rough proxy measure. This assumes every website request will require an authoritative request to your domain (and ignores non-web lookups for your domain, such as email, etc).

To account for the recursive nature of DNS resolution, you can multiply the requests to your domain by a factor (between 1 and 2). This is difficult to determine more precisely, so it’s up to you to decide how conservative to be in the estimate.

With this data in hand, you can use the Sustainable Web Design method to calculate your emissions. Assuming that the average DNS request is about 500 bytes, you can calculate the total bandwidth by multiplying this by the number of requests calculated above). Estimate the electricity consumed to serve this data by multiplying by the standard factor 0.81 kWh / GB.

And then finally convert this electricity use to carbon dioxide emissions (CO2e) by applying appropriate electricity emissions factors. If you know emissions factors from electricity in the data centers serving your requests you can use that. Or you can use the global average carbon intensity of electricity: 442g / kWh.

As a worked example, assuming that a domain received 10 million DNS requests per year, we could estimate its carbon footprint to be:

- 10M * 2 * 500 bytes = 10 GB

- 10 GB * 0.81 kWh/GB = 8.1 kWh

- 8.1 kWh * 442g/kWh = 3.6 kg CO2e/year

Managing your domain’s carbon footprint - the easy way

The easiest way to manage your carbon footprint is to let someone else worry about it. By selecting a carbon neutral DNS provider and web host (see our list of eco-friendly retailers) you are choosing a partner who can take account of this for you. Also we would encourage you to select a carbon neutral TLD (like .eco!) for your domain names.

Here are some of the things that we are doing to minimize the carbon footprint of the .eco registry:

- Measuring and publishing our carbon footprint annually

- Optimizing the efficiency of our digital infrastructure and web properties

- Offsetting any residual emissions by overcompensating for our impact and investing in a diversity of offset projects

There are lots of opportunities to minimize the impact of your systems and infrastructure – and while it’s only a small piece of the puzzle, your domain name is a good place to start.